My name is Roberto Allen Ackerman and I am a Loser.

I wasn’t always a Loser. In fact, before puberty and the horrific, mortifying bodily betrayals that followed, I was one of the Popular Ones, one of the Elite, but I suffered the fires of biological change poorly and descended into the darkest regions of nerd-dom.

But no more. I have a plan and the plan begins now. And it starts with running. Oh, yes, you’re going to have to run again, Roberto. Run, Roberto, run!

So next year will be different. I will be well-liked. I will be popular. I will be welcomed with open arms into the circle of the socially Elite because I am a survivor.

I am a winner.

At least, that was the plan, until the aliens invaded.

Or, more accurately, when they moved in down the street from me with their huge fleet of big U-Haul trucks and their beautiful daughter, Hanna. Then things really got out of control.

But I’m getting ahead of myself.

The most important thing I will tell you is that I am a fourteen-year-old male human being. Another thing I will tell you is that I am terrified of girls. Human girls, Paz girls, Virian girls, and Holden girls. Every one of the four hominoid species from the Local Stellar Group. Each and every girl. Human girls the least, I think, and Paz girls the most.

Or maybe the most important thing I should tell you is that until this summer, I was a catastrophic, Category 5 Geek. I wasn’t always a geek. I’m not even sure when I devolved into geek-dom. Throughout grade school, I was one of the cool kids: funny, good-looking, popular. Then puberty hit.

No one told me that when the flood of hormones sent my various glands into overdrive and I started producing sweat, body hair, and military-grade grease at an industrial rate, I would need to upgrade my bathing frequency and other hygiene routines from once or twice a week to once a day. At the same time, my toothbrush and I had only a passing relationship. Clothing, fashion, and I had none. Physical coordination came as naturally to me as ballet does to a rock. I have two older brothers who might have helped me navigate the changes and betrayals of my body, but they were much older than I and already off to the Frontier when hygiene, social acceptance, and I parted ways.

My dad apparently had seen this happen with his first two sons: the loss of skills, social and physical, and the overall descent into nerd-dom. His answer? Sports and Scouting. Not a bad thing in itself, right? He got me into sports as soon as I could, well, hold a xistera. Don’t know what a xistera is? Neither did I, but by age four I was willing to hold just about anything I could swing at the cat, glassware, and other breakable and/or terrified objects. More on that later.

Scouting could have saved me. It taught me a bunch of stuff like wilderness survival, honor, and paramilitary tactics, but in fact, it led to my final, catastrophic downfall. Sports could have saved me, maybe even put me on the road to popularity and elitism. Dad could have put me in football or basketball. Either would have been a sure-fire ticket to the In-Crowd. He could have put me in baseball or golf. Either of those would have been socially acceptable. Or he could have put me in, say, fencing or bowling. Even those might have been a suitable choice. Well, OK, not bowling. But no, in a misguided attempt to prevent my fall into social rejection, he chose jai alai.

Yes, jai alai.

You can’t even pronounce that, can you? Well, neither could I nor my normal friends. But my great-grandfather could. And so could my grandfather. And my father. And my two older brothers. And eventually, so could I. And to help you along and keep you from skipping over it every time you see this, it’s pronounced hi-li.

It turns out my great-grandfather was a Basque and loved the sport. A what, you ask? A Basque, a man from a small community of people who had fought Spain for independence for, like, a million years. I think they still might be doing it today, just for fun and to keep the ol’ Basque tradition alive. Anyway, the Basque folks love jai alai. They love it so much they sing songs about it. Really bad songs. And it’s so popular outside the Basque community in Spain that exactly two other countries host hi-li tournaments: Brazil and the United States.

Yep, that’s it. No one else. In fact, only two states in the U.S. actively field hi-li teams: Florida and New York. In fact, curling is more popular than hi-li. Yes, curling, the sport—the Olympic sport, mind you—that has a bunch of people sweeping an ice rink with little brooms while sliding a big honking stone onto a target. An Olympic sport. Sweeping ice. Sliding stones. More popular than hi-li.

So let’s get down to the hilariously painful details. First, there’s the uniform. It looks like a cross between what might be worn by a jockey and, perhaps, an evil circus clown. It consists of a nice, very white pair of polyester slacks with flared legs and as colorful a silken polo shirt as your team or club can imagine. My team, the New York Conestogas, chose a subtle combination of crimson red and fluorescent green. Our opponents called us the Intergalactic Tomatoes.

And you get a helmet; not a cool one like a football player, but one that looks like a perfectly round bowl with a chin strap. Like something you might give a three-year-old about to take his first bike ride or a retarded child who falls down a lot. Then there is the xistera, also called the basket. This is a long cuplike device that you strap onto your forearm and use to catch the pelota (that’s the ball). The xistera has the effect of making you look like one in a chain of those monkeys you used to hook together when you were four. You know, from the ever-popular Barrel of Monkeys game? So, you use this xistera to throw the pelota down the impossibly long court in an effort to either make your opponent drop the ball, let it bounce too many times, or pulverize one of his major organs. Because that ball? That little hard rubber ball with the density of lead, or maybe uranium? Well, it’s moving at roughly 170 miles per hour, and if you get hit by it, well, let’s just say it’s an experience you won’t soon forget. Fellow hi-li players call it the Great Bruising. I call it child abuse.

So in summary: the game is like racquetball, except you wear clothes better suited for a creepy clown (and aren’t they all creepy?), an escapee from an insane asylum, or a homeless person; a helmet meant to make you look like equal parts nerd and retard; a two-foot “barrel of monkeys arm”; and dodge a viciously hard rubber ball moving at 170 miles per hour that can hit you with the force of a cannon and easily knock out one or both kidneys if you’re not careful.

Fun!

But hi-li was a family tradition, and by the Great Lord above, I was going to play. So play I did, and it turns out that I was pretty good. Good enough to brag to my friends about making a chula shot? No. Good enough to wear my god-awful hi-li uniform to school? No. Good enough for hi-li to propel me to the uppermost heights of the popular Elite? Absolutely, unconditionally, and not under any circumstances—no.

I may have been good enough to win tournaments and a limited amount of glory from my equally cursed hi-li teammates, but somehow I knew that trying to explain this arcane and baffling sport to others, or to leverage that into popularity at school, was just not going to work. It would be like trying to brag about being the best polka dancer, an expert accordion player, or the proud owner of the state’s largest dead bug collection. All that was likely to do for you is earn you awkward looks of pity and perhaps a few beatings by the less sympathetic bullies of your school. However, I was very good and had hi-li been an accepted and well-known sport, I might have been one of the popular kids at school. But it wasn’t, and I wasn’t.

And finally, when I hit sixth grade, my sense of style—so keen before puberty, when I could sport cartoon characters and science-fiction-themed clothing and be considered hip—failed me utterly, and as I wore more of the same, my descent into nerd obscurity was nearly complete.

You might think I had hit bottom with the Bad Hygiene, Bad Social Skills, and Bad Clothing Trifecta. You would be wrong. I was unwashed, unclean, and unwanted, but I had not completed my transition to an F1 Nerd, a Finger of God Nerd, just yet. It took the first day of seventh grade to execute that last herculean step into total rejection.

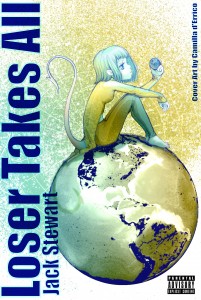

Like what you’re reading? Want to read more? Buy the Kindle book here!